"Everything about them, without them"

Public Health without the Public: The Aesthetics of Consensus-Washing and the Politics of Science

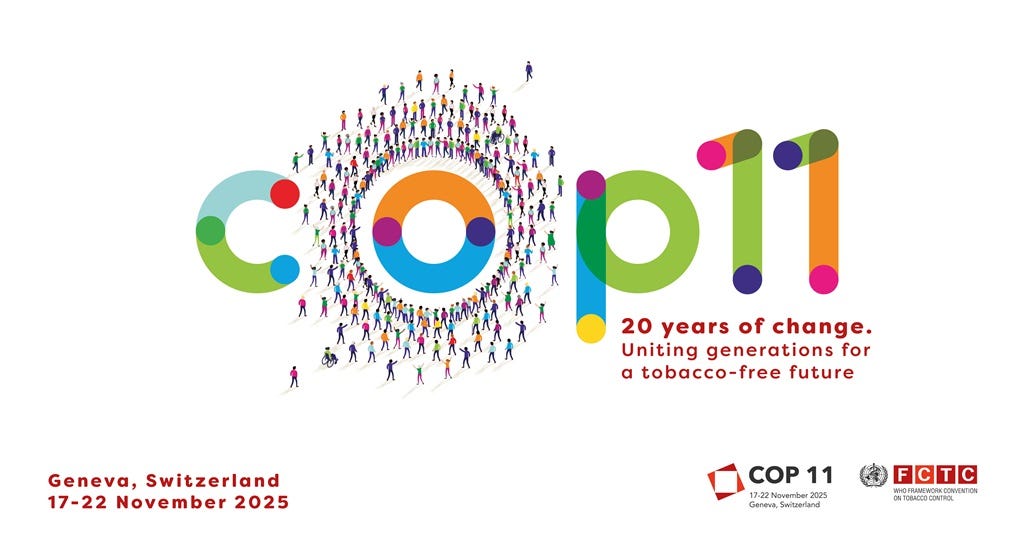

At the center, an “O” turned into a ring. Around it, diverse bodies orbit like iron filings to a magnet. They draw near, graze the edge, offer a nod. No one crosses.

The void at the center gleams: not absence, but an armored threshold. The spiral guides, orders, and tames the gaze. A multicolored palette promises plurality. The sans-serif smooths down the roughness. The slogan legitimizes, certifies like a seal of its age. Everything seems to say “welcome”, yet the design seeds a countermeasure of its own: the center is off-limits.

Unity and progress, yes. But choreographed into a proximity without access. Diversity is offered as set dressing: differences are displayed, not because they can rewrite the script. Color pacifies, the slogan summons, and dissent remains out of frame.

Thus, change is narrated as tranquil continuity. An aesthetic of order is imposed: nothing out of place, nothing off-key. In that stillness, technocracy takes the helm: participation rationed, consensus as the horizon, dissent reduced to white noise.

No image reaches the gaze neutral. All arrive with the patina of history, the scent of their era, ideology in filigree.

On the surface, we see strokes, colors, and a framing that feigns innocence: that is the signifier.

Underneath, with a breath of its own, meaning and its retinue of connotations— values, affects, ideologies, and biographies. Ideas spark when the gaze grazes the image. And the image is no window; it is a mirror with a memory, an artifact that betrays us even as it claims to represent.

Looking, then, is translation.

And every translation is historical, embodied, neurological, and political.

The Uncrossed Circle

We live immersed in a soup of dots, lines, shapes, colors, and pixels. In that texture-saturated buzz, the image is no ornament; it operates.

It is a meaning-making device. Veer a millimeter from the reflection and you see that the image isn’t in things but in the mind that processes, molds, and orders visual experience. It catches the burst of light and emulsifies it with memory, habit, and desire. It interprets the world and, in so doing, shapes us.

Even the trivial carries a political charge. A logo, that mark that slips across the retina without asking permission, rarely asks for thought. We accept it as a useful, neutral badge. Yet it works with machine-like discretion: a high-powered ideological device, capable of normalizing values, drawing lines of belonging, mapping allegiances, and producing affect.

Even the logo we take as innocuous—clean, obedient, neutral—accumulates sedimentation of meaning. Hold the gaze, and what seemed an ornament opens into a map of power: decoration unfurling as economic-political cartography. Such is the case with the official emblem of COP 11 — the Eleventh Conference of the Parties to the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control — a mark devised for identification that, in practice, organizes allegiances and manufactures attachments.

At first glance, the logo celebrates: distinct bodies in a circle, a multicolored orbit that promises a future, a resplendent slogan. But tighten the focus, and the image inverts.

With Bourdieu breathing down your neck—or from the margins of public health— the compositions betrays another choreography: an armored center, window-dressing inclusion, and a graphic harmony that shields itself as if it feared dissent.

The graphic gesture of the COP11 emblem summons—whether with feigned innocence or excessive devotion—a stubborn old figure: the center of power. In feudal maps and mandalas, the center is not a point; it is a hierarchy. It confers rank and sacrament. It fixes distance. It decides who approaches, who skims the edge, and who remains in orbit. No one enters without permission. No one enters.

The Aesthetics of Consensus, the Politics of Silence

Here, harmony patrols like a velvet police force. Diversity is displayed as proof of openness, but access to the core remains armored. Consensus, turned into style, sands down the edges of dissent until they read as decoration. Public health ceases to be an agora— where debate happens—and becomes a chapel—where one obeys.

The paradox pinches. The slogan announces “Uniting Generations”; the image, by contrast, sketches a disciplined periphery, eyes fixed on an inaccessible center.

Image and procedure mirror each other with a rough exactitude: a COP 11 underwritten by public and philanthropic funds, convened behind closed doors, with a hand-picked press corps and scant representation of those subject to regulation. Stagecraft and method align: unity on the poster, exclusion at the core.

The organizer (the Secretariat) advances a defensible argument: to safeguard the integrity of the process against harmful interference and conflicts of interest—a principle enshrined in the FCTC—and to preserve negotiating effectiveness. But that rationale does not excuse opacity, secrecy, and exclusion. The rule should not be allowed to harden into a stratagem.

Who draws the boundaries of the bodies authorized to cross the circle’s threshold? What forms of knowledge are kept outside the admitted canon? Which biographies are pushed to the symbolic, historical, and material periphery? Public health—a public good by definition—presents itself as a professional liturgy: sterile stagecraft that sands down disagreement and erases the contours of its own exclusion.

The log preaches unity; the staging apparatus regulates distance.

If the center won’t grant passage in the image, it won’t in the procedure either. There lies the uncomfortable lesson: when consensus dresses up as style, it expels what public health most needs to hear—complexity.

Perfomartive Inclusion, Structural Exclusion

The emblem stages a benign showcase—colors, gestures, ages, a wheelchair—as if display amounted to equality. Diversity is kept at the edge. It does not deliberate; it performs. It does not participate; it represents. Pure choreography, compliance with protocol. This is what Sara Ahmed calls diversity work: the management of difference at the surface, an administered openness with the power structure left intact.

The logo’s scene is mirrored in the method. Those who carry these policies in their bodies—users of harm-reduction programs and products, collectives that accompany concrete lives, pragmatic scientists, physicians who look into faces still alive—are left in the corridor, if not the waiting room. NGOs are admitted by vetted invitation, and the debate unfolds behind closed doors. Deliberation without a square: democracy sterilized in a lab coat.

The result is a public-health apparatus that seems to fear the very public it claims to serve.

Pierre Bourdieu warned that there are violences that never raise their voice; they naturalize themselves until they pass for landscape. They prevail not through coercion but through habit. That is the trap of symbolic violence: it enlists the complicity of those who endure it. The emblem works in that key. Beneath its benign multiculturalism, it cushions conflict; with the promise of unity, it digs a moat between those who set policy and those who carry it in their bodies. The logo operates as a silencing device.

If greenwashing launders harm with cute leaves and slogans, this design rehearses its own trick: consensus-washing. A veneer of color that passes off as openness, which, in practice, amounts to managed opacity.

The question is not whether the logo speaks, but what it leaves unsaid. What guarantees of access, transparency, and accountability are kept out of frame? What reforms would make it untenable for this aesthetics of consensus to coexist with closed-door procedures?

What if the circle were a cage?

Let’s invert the analysis. Turn the image inside out. Perhaps the blockage isn’t at the edge but within: a narrow center, a constricted vertical governance, self-asphyxiating. It isn’t that the entry is denied; it’s that the world doesn’t fit. Its biographies, its forms of knowledge, its dissent overflow the ring like water at a bottle’s neck. A conceptual cage: the old grammar of vertical control, unable to accommodate the world’s complexity.

If the center is a cage, the task isn’t to loosen the bars; It’s to change the figure. Redraw power’s blueprint—off-center. From here arise operational questions: what institutional—and visual—architectures can enable porous processes, with effective public deliberation and the circulation of knowledge from the margins?

At COP11’s periphery, those who unsettle the script are the ones who are forbidden to speak: harm-reduction specialists, collectives that stand alongside real lives, pragmatist scientists, physicians who look into faces that still breathe.

If the periphery holds situated knowledge, what does policy sacrifice when it plugs its ears? This is not (only) a dispute over methods; it is the ledger of life. Who is counted among those who get to define that “tobacco or nicotine-free” future—and who is left out?

The Paradox of Conflict-Free Public Health

Public health, if it honors its name, is an agora, not a sacristy. Air, noise, argument. It is—or should be—a space of open deliberation and collective construction. Common work made with dissent that is heard and agreements hard-won. Without plurality, there is no care; without listening, no ethics.

Consensus without conflict is no virtue; it is a white-glove imposition. It doesn’t celebrate; it masks. If we accept consensus as an aesthetic, we forgo politics as care.

The question is not whether conflict will arise; rather, it is how to provide a framework for it—clear rules of access, open deliberation, and accountability—that opens the center, both in the logo and the method.

The COP11 emblem, tidy and genial, packages an aseptic future. It sells a tobacco-free future, yes; a frictionless one, too. The promise of union becomes an enclosure: a “we” contemplated from the inside, in the mirror, while the periphery remains outside, in ritualized waiting.

“20 years of change” promises a time in transit. Yet the emblem doesn’t move: no trace of a journey, no breaks, no visible metamorphosis. Change is declared; the form does not move. The words move; the image stands still. How are generations tied together if there is no bond here, no trace, no lineage traced? There are no hands reaching one another, no baton-pass between ages. The phrase promises union; the image belies it.

Read the Symptom, not just the Symbol: The closed-circle metaphor

Institutional discourse chases semantic closure: it armors meaning. That’s why reading symbols as symptoms lets air in. And it’s an act of resistance. The COP11 logo is not innocent: it does not illustrate; it disciplines. It isn’t just another illustration: it is both manifesto and device—declaration of principles, creed, and border at once. It signals, without saying so, who gets in and who stays out.

The ring condenses closure. A public health without openness, democracy, and an aversion to change—the very shadow the emblem hoped not to cast.

The circle is an ambivalent symbol, a two-faced creature. It offers unity and shelter, but, depending on context, it flips: the rounded line becomes a wall, an enclosure, a private preserve.

Here, the ring fixes an interior of power—delegates, States Parties, credentialed civil society, aligned journalists, and an exterior kept waiting. Entry requires benediction.

Thus, the FCTC’s COP11 emblem maps exclusion: a closed ring and bodies at the edge for a process that proclaims “Uniting Generations” with the walls intact.

Graphic design isn’t neutral; at times, it is a mirror for the unsayable. Which is why this emblem, paradoxically, is its most honest statement.

* * *

I checked the post with It's AI detector and it shows that it's 92% generated!

Brilliant