LOOK AT THE FACES OF THOSE WHO STILL BREATHE

A Biography of Restless Science

His trajectory didn’t follow the straight logic of academic progress, nor the predictable path of an institutional career. It was, instead, a constellation of deliberate detours—each one driven by questions as uncomfortable as they were illuminating. Questions that are not answered in technical reports or official speeches, but in the lived reality of those who inhabit the margins.

What do we do when data—cold, hard, irrefutable—contradict the moralism of politics? How should we act when saving a life means skirting, or even defying, the boundaries of legality? And what does it truly mean to care for someone—not from the safety of protocol, but from the raw exposure of commitment?

This text traces not only the existential and biographical path of its subject. It also follows, with the same pulse as his restless and compassionate gaze, the ethical and professional arc of a life that has been shaped by questions that refused to be domesticated. It unfolds in brief chapters—almost like scenes—that do not merely document events: the lived experience itself interprets them, interrogates them, situates them within the intimate time in which a single decision can alter the course of a life.

It is a journey that moves from the young researcher who learned to listen without the reflex of judgment, to the academic who built spaces of knowledge within the cracks of prejudice. From the editor who challenged the hierarchies of science by opening dialogues where once there were borders, to the professor who now teaches—with the quiet conviction of someone who has lived what he says—that reducing harm from tobacco is not just a matter of public health policy, but a concrete affirmation of the human right to live with dignity.

His career was not a straight line, but a wall-less labyrinth—where every answer opened onto new forks in the road. He never chose the comfortable path. The protagonist of this story has always been, in his own way, a disquieting voice. He has said what many prefer to leave unsaid. He has defended alternatives to tobacco consumption in a field dominated by dogmatic certainties, where dissent is often punished with discredit.

And he did so not out of opportunism, nor for the aesthetics of disruption, but because data, evidence, and ethics converged with the force of an undeniable imperative. His cause is not nicotine. His cause is autonomy, dignity, the right to live with agency over one’s own body—and against the imposition of preventable suffering.

“Whose side are you on?” he once said. “Social research needs to engage with people and give voice to those who are often unheard. To paraphrase the American sociologist Howard Becker, what do things look like from the ‘other side’?” It’s how one of his lectures to sociology students began—but it might as well serve as the epigraph to an entire life. What follows is the portrait of someone who has refused to measure harm merely. He has chosen to understand how it is produced and to reduce it. And in doing so, he has offered not only data or analysis, but also his body, his thought, and his voice.

Summer, 2024. Warsaw, just before dawn.

From the fourteenth-floor window, the city unfolds as if time were brushing against its surface without quite wounding it. It’s not that it remains untouched—it has simply learned how to mask its erosion, like someone applying makeup over a wound still open.

There’s something in its stillness that defies chronology: the same buildings, the same streets, the same underground passageways breathing beneath the asphalt like urban veins—hidden, but alive.

Even the people, seen from this height, do not walk so much as perform an ancestral gesture, as if each step carried the memory of other steps, wrapped in a mineral silence that has yet to dissolve, even after more than a decade.

Nothing appears to have changed. And yet, everything has.

The conference auditorium, still empty, holds a dense, almost tactile silence. A silence that does not merely hush, but gathers. As if within its walls, not only unspoken questions had accumulated, but also truths repeated to the point of exhaustion, and voices that, year after year, have found in this room their only refuge. Voices that do not fit within protocols or reports. Fractured voices. Urgent ones. Displaced. They have no place in the corridors of power, but here—in this space of red carpets and subdued lights—they leave traces on the walls, like echoes that refuse to die, like breaths that never fully dissipate.

In a few hours, this place will fill with bodies and words. There will be talk of smoking and nicotine. Of human rights. Of science. Of that shared particularity that cuts across the lives of billions: hope.

But now, as the technicians adjust the lighting, as the last speck of dust is vacuumed from the floor and the red chairs align with the precision of a silent verdict—as if each one were about to witness something still without a name—he walks alone through the carpeted hallways of the Marriott.

He is nearly eighty now, but still carries in his body the drive, the tremor, and the urgency of first times. The urgency of someone who never surrendered to routine. Because it all began with a question that never stopped burning: Why do some people suffer more than others, why are some people more at risk… and why does the system allow it?

London, 1967.

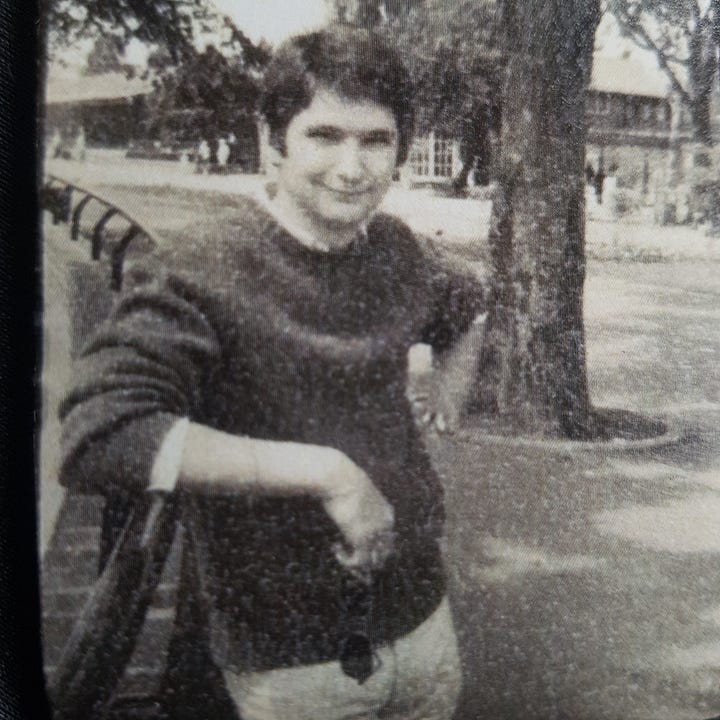

Amid narrow streets and broad avenues marked by history, the world simmered in a crucible of political, psychedelic, and cultural ferment. But inside the Addiction Research Unit at the Institute of Psychiatry in London, a young British sociologist seemed immune to both the glamour of the moment and the lingering poison of stigma. Gerald Vivian Stimson was just twenty-two when as a newly hired researcher he immersed himself in a world most people preferred not to see: a world of dim corridors and vivid colors, inhabited by bodies the state had chosen to regulate through prescribed heroin—not out of compassion, but as a form of control.

And instead of observing from the sterile distance of academia or the medical clinic, he chose to move closer.

“I wanted to understand,” he would later say, “how people addicted to heroin managed their lives and their drug use.”

“They were people with routines, with agency, with fear, with tenderness and thoughtfulness. What I discovered was in the stories that needed to be heard.”

His first major study, published in 1973, mapped the profiles and behaviors of people using heroin who were receiving care in London clinics. At the time, it was rare to encounter a perspective untainted by moral judgment. But Stimson was already looking through the inquisitive lens of sociology, driven by an uncomfortable suspicion: that what was being called “addiction” was neither an individual failure nor a moral plague, but something far more complex.

There were structures.

There was inequality.

There was abandonment.

Behind every needle, an invisible chain began to reveal itself—of political decisions, state negligence, and fractured lives. And within the data, another, deeper truth started to take shape: the wound was not in the body. It was in the system that had left it exposed.

It was in those corridors that he learned how to listen—not with the haste of a clinician or the detachment of a researcher, but with something deeper. A kind of listening that involved the body, the doubt, the surrender of someone who knows they are incomplete.

As if each account were a thread in the great social tapestry—not merely to be unravelled, but to be felt in its texture, its knots, its empty spaces, and its silences.

What followed were years devoted to studying the relationship between doctors and patients, the treatment of healthcare professionals who were themselves struggling with addiction, and the impact of public health policies on the most exposed, most forgotten bodies.

Far from retreating from the margins, Gerry—as he is affectionately known—returned to them again and again. Not as an outside observer, but as someone willing to be moved, through and through. As someone who had come to understand that harm can only be grasped—and perhaps repaired—from within, and alongside others.

“The closer I got, the more I realized the limitations of seeing people as addicts, patients, or criminals. They were not passive recipients of treatment or punishment, they were people negotiating a complex world of drugs, everyday life, and medical and judicial systems”.

By the mid-1970s, after a brief period at the University of Swansea (1971–1975), he returned to the Addiction Research Unit—this time as a lecturer, and set out to find out what had happened to the heroin users he had met seven years earlier. This reaffirmed his view of the complexity of the relationship between drug use, personal life, and the systems that seek to control addicts and addiction. “Contrary to a prevailing view that ‘once and addict, always and addict, and of inevitable deterioration’ ” he said, “there were extraordinary tales of people moving into and out of drug use, and of some people who managed to lead quite ordinary lives while using heroin”.

His next move was into teaching sociology at Goldsmiths’ College in London, where he moved in 1978. The next decade was spent sharing his insights with students.

But something inside him had begun to stir. Academia offered the comfort and safety of observation, when what he truly needed—what was calling to him from deep within—was to act.

How can one study pain without confronting its causes? How can one bear witness to a wound without trying to heal it? Scientific attachment offered him a method, but no solace. Nor all the answers. And he wasn’t searching for neutrality. He was searching for meaning.

That inner dilemma became intolerable a few years later, with the arrival in 1986 of a shadow that would raze certainties, bodies, and biographies: HIV/AIDS.

What had once been theory became urgency. What had been analyzed turned into a trench. It was no longer about understanding—it was about taking a stand. About being there. About not looking in from the outside.

And so, the young man who had once set out to understand how people who used heroin behaved would come to embody a new ethic —one in which saving a life mattered more than punishing a behavior. An ethic of care over control. Of listening over judgment. Of dignity over fear. And of the body—once again—as the first and final terrain of politics.

Warsaw. The auditorium is no longer empty.

Voices in English, Polish, Spanish, Arabic. Professors, scientists, activists, and nicotine users—the murmur of the world begins to form a collective breath, slowly becoming audible.

Gerry Stimson steps onto the stage with a folder in hand and a calm gaze. He is no longer the young man who set out to understand. He is someone who has learned—by listening to what others discarded—that compassion is not an academic weakness, but a deeper, more radical form of knowledge.

“People are at the core of harm reduction,” he says, “it’s people who are leading a silent revolution in the way nicotine is consumed. This is public health leadership by the true experts, people who are affected by smoking, rather than by so-called Public Health experts.”

Liverpool, winter of 1986.

In a city still wounded by industrial restructuring and scarred by unemployment, a small group of professionals gathered in a plain room. Nothing about the setting seemed remarkable: grey walls, barely adequate heating, lukewarm coffee, and tea.

And yet, in that unadorned space, an idea began to take shape—an idea that would change the course of public health: What if, instead of punishing people who use drugs, we helped them survive?

Among those present was Gerry Stimson. He brought no certainties—only questions. And that was enough to crack the logic of punishment. To ask that question, in that context, was already an act of insurrection.

The 1980s were a time of transformation—but also of fear. The emergence of HIV/AIDS shook the foundations of medicine, politics, and human relationships. In the United Kingdom, cases multiplied, and with them, a wave of moral panic.

Many authorities responded with abstinence campaigns, with silence, with exclusion. But some chose a different path. A small group of researchers, doctors, and activists understood that the virus could not be confronted with disdain. Action was needed—and urgently.

With compassion, yes, but also with rigor. With speed, but without losing the soul. Gerry Stimson was one of them. “What can we offer the thousands of people who inject drugs, who are unable or unwilling to stop injecting, despite the threat of imprisonment and the often unrealistic aims of abstinence treatment?” he said. “We cannot abandon them, but need to find ways to help people reduce their risk of HIV infection, and indeed other risks such as overdose”.

At the time, Gerry was conducting research on addiction, risk behaviors, and community health. But he was no longer observing the world solely through the lens of a researcher: he had learned to read what the data left unsaid.

He knew that drug use was rarely an isolated act—it was a response, sometimes precarious, sometimes desperate, to realities that were often brutal and always uncomfortable.

When HIV began moving through the streets, he realized that observation was no longer enough. One had to get involved. One had to move. “It was time for services,” as Tim Rhodes would put it, “to get out of the agency and on to the streets.” And the researchers went out with them.

It was in this context that Gerry met Pat O’Hare, one of the key figures in the emerging harm reduction movement in the UK. O’Hare was leading the Mersey Regional Drug Training and Information Centre, from which some of the country’s first needle exchange programs were launched.

Gerry was invited by the government to evaluate the Mersey program and others recently established elsewhere in the UK . What he found was not just effectiveness. What he found was humanity: a gesture of care in the midst of abandonment. A policy that, for the first time, did not speak about people who use drugs, but with them.

“It was an adventurous and dangerous time,” he would later recall. “What was at stake was the right not to die, and the public health and human rights imperative to help people, including people who inject drugs, to avoid their risk of HIV infection.”

Between 1986 and 1989, the Merseyside region—Liverpool in particular—became a pioneering laboratory for what would later be known as harm reduction. Gerry was not simply another technician. He was a witness with a voice. A researcher who didn’t just record data—he transformed it into ethical arguments.

Based on the evidence, he advocated for strategies that seem obvious today, but at the time were seen as outright provocations: distributing sterile needles, teaching safer practices of use, prescribing methadone, and approaching sex workers without judgment or correction. In a time marked by moralism and fear, these actions were far more than public health interventions. They were acts of dignity.

The British model began to draw attention from other parts of the world.

In 1989, Gerry took part in launching the International Journal on Drug Policy, whose very first issue already spoke—tentatively but clearly—of a “social movement for drug policy reform.” At the time, he didn’t yet know it, but that movement would become more than a space of struggle. It would become his home. A place from which to think, to accompany, and to resist. Something had changed for good: it was no longer enough to study reality. It had to be contested.

Paris, 1989.

At a conference on HIV and drugs, a young doctor approached him with a question, almost in a whisper:

—“Do you really think it wise to hand out syringes?”

Gerry smiled, without drama.

—“Yes, because it works. It helps people to help themselves.”

London, 1990.

In a dark-brick building in the Fulham neighborhood, the second-floor windows stayed lit well into the night.

No sterile reports were written there. Drug users were not counted as if they were statistical waste.

At the newly founded Centre for Research on Drugs and Health Behaviour, Gerry Stimson had created something more than an academic institution: he had built a place where thinking was also a form of resistance.

A trench lined with books.

A science unafraid to get its shoes dirty.

After the intense years in Liverpool and the vertigo of the HIV/AIDS emergency, Gerry had come to understand something fundamental: real transformation requires more than courage. It needs structure. Evidence. Conceptual friction. And, above all, a space of its own.

Out of that need came the Centre for Research on Drugs and Health Behaviour, eventually part of Imperial College London—one of the country’s most prestigious scientific institutions.

It was, in a way, a revolutionary gesture: to insert harm reduction—that uneasy ethic born at the margins—into the very heart of the British establishment. To bring insurrection into the corridors of power, without raising one’s voice, but without giving up ground.

There, Gerry assembled a team as rigorous as it was rebellious, with figures like Tim Rhodes—a restless sociologist who shared his deepest conviction: that theory and practice must be intertwined, that evidence must meet the street.

Together, they studied risk behaviors, designed community-based interventions, and analyzed public policy. But above all, they listened—not as a methodological gesture, but as a political decision.

Because one of Gerry’s most radical innovations wasn’t found in a peer-reviewed article. It was found in the field: integrating active drug users as part of the team, as experts in their own territory.

They were not objects of study. They were part of the team.

“It’s not about studying people,” he used to say. “It’s about researching with people.”

The phrase may sound obvious today, but in the 1990s, it was a declaration of war against the paternalistic logic that still dominated public health. Gerry championed mixed methodologies, questioned traditional epidemiology, and defended—with both rigor and tenderness—the ethical dimension of fieldwork.

Flawlessly designed scientific articles, published in prestigious journals, could not whitewash the pain. Evidence, he insisted, had to have a face. And a voice.

Meanwhile, the harm reduction movement was gaining ground. International conferences—such as those organized by Pat O’Hare—brought together, for the first time, professionals, drug users, activists, and policymakers in the same room. It wasn’t just an academic community. It was a social alliance. A common language born of radically different experiences.

Gerry was there. Observing. Writing. Intervening. And above all, asserting—with every gesture—that another kind of public health was possible.

It was then, in that tense space between science and activism, that an unexpected proposal arrived: to take over, alongside Tim Rhodes, the editorial direction of the International Journal of Drug Policy. The year was 2001. Their first issue together was Volume 12, Number 1. But more than an issue, it was a declaration. A boundary being pushed outward.

“We didn’t want the journal to be a bulletin for the already converted,” Gerry would later recall. “We wanted it to become a global academic reference.”

They knew that language was also a trench. And that contesting the discourse was as urgent as designing interventions. Publishing was another form of action. And they succeeded.

Under his leadership, the International Journal of Drug Policy shed the pamphleteering tone of its early years and became a rigorous, courageous, and deeply committed platform. Gerry rejected speculative pieces, defended clarity of language, and pursued one goal above all: that the reader would learn something new—and that, somewhere, that learning might change a life.

Barcelona, 2003.

At a meeting with public health officials, someone asked him:

—“Professor Stimson, do you really believe that people who use drugs are interested in protecting their health?”

Gerry smiled gently, without superiority or haste.

—“I don’t believe it. I know it. I’ve seen it. And the point is that harm reduction is a partnership, it’s not about experts delivering services, but of engaging with people to help them protect their health.”

The years he spent leading the Centre for Research on Drugs and Health Behaviour and the International Journal of Drug Policy were not just an academic chapter. They were the time in which Gerry Stimson moved from method to movement.

He never stopped being a scientist. But by then, he had come to understand that science without justice is just another way of preserving the status quo. And he had come to dismantle it.

The Right to the Unwanted

There is a right no one wants to name. It lives in the margins, in the choices others condemn, in the substances society prefers to bury. Gerry Stimson made it visible.

In 2004, Stimson stepped down from his academic post at Imperial College London. Not because he was tired, but because he understood that the work didn’t end in lecture halls or scientific journals.

Evidence, he believed, only matters if it can be translated into change.

That same year, he became executive director of the International Harm Reduction Association (IHRA), based in London. For six years, he led global campaigns to have harm reduction recognized not just as a technical tool or a policy option, but as a non-negotiable human right.

Under his leadership, the International Harm Reduction Association worked closely with United Nations Special Rapporteurs on the Right to Health, helping to secure public recognition of what had long been considered unthinkable: that access to clean syringes, substitution therapies, and non-stigmatizing care is an essential part of the right to health.

But while that victory was being consolidated, another front was quietly emerging—with fewer allies, and harder to defend, even among supporters: tobacco.

“Sometimes,” he observes, “the same people who defended harm reduction for heroin and other drugs became prohibitionist crusaders when it came to nicotine.”

Gerry saw the contradiction. And once again, he chose to cross the line that separates what is popular from what is right.

In 2010, he founded, with Paddy Costall, Knowledge-Action-Change (KAC), an organization created to foster new forms of dialogue around public health—a conversation grounded in rights, evidence, and personal autonomy.

From there, he began advancing what would become his most significant contributions: the Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction (GSTHR), a project designed to document and report on the impact, challenges, and opportunities presented by lower-risk nicotine products. Alongside this, K•A•C initiated the Tobacco Harm Reduction Scholarship Programme to help train up a new cadre of people active in communicating and educating about the need to enter a space where conventional tobacco control was not succeeding in facilitating a switch from smoking to safer nicotine products.

The field had changed, in some ways. But not his conviction. Gerry keeps on asking the same question: Are we willing to offer solutions that work, even if they make us uncomfortable?

In many countries, the answer was silence. Or worse—prohibition.

While some health organizations adopted repressive policies against vaping, snus, and heated tobacco products with little to no debate, Gerry has returned to the essentials: reading and interpreting data, speaking with users, listening to their stories. Building bridges between science and human rights.

“Harm reduction,” he insists, “is about recognizing that people are already consuming substances—and that we have a moral duty not to condemn them for it, and a parallel duty to help them avoid risk.”

Geneva, WHO conference hall, 2018.

Outside, journalists waited. Inside, carefully selected delegates discussed updates to the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC). They spoke of taxes. Of bans. Of eradication.

No one mentioned rights. No one spoke of autonomy. No one uttered the words that hung silently in the air: the one billion smokers who would not succeed in quitting.

A repressive discourse dominated moralism in tobacco control.

Gerry was not allowed to attend the meeting. Like other people speaking up for tobacco harm reduction, he was excluded. After a lifetime dedicated to public health, Gerry Stimson had reached a troubling conclusion: language had been hijacked.

Where once there had been talk of relieving suffering, now there was talk of “eradicating consumption.” Where once there had been talk of accompaniment, now there was talk of coercion.

The same exclusionary logics he had fought against in the 1980s were back—more subtle, more technical, but no less violent. This time, disguised as science.

The dominant discourse rested on a seemingly untouchable premise: public health as a form of protection. But Gerry sensed something darker behind that word. A veiled moralism that sought not to empower, but to discipline.

It wasn’t about care—it was about correction.

It was at that moment that his scientific activism entered its most controversial phase: the open defence of products like vaping, snus, nicotine pouches, and heated tobacco as legitimate, effective, and substantially less harmful tools.

Not as a provocation, but as continuity. Because for Stimson, harm reduction had always been a matter of principle, not popularity.

And then, as always happens when someone dares to challenge a dogma, he was accused of serving the industry.

The data didn’t matter. Nor did his decades-long track record. Dissent alone was enough to turn a scientist into a suspect. For many, questioning the dominant narrative was more dangerous than ignoring the evidence.

It wasn’t new to him.

He had already seen how those who defended sex workers or people who use drugs were discredited. He knew that giving voice to the excluded often came at a cost.

But this time, the terrain was even more slippery. Because the adversary wasn’t the state. It wasn’t the conservative right. It was the public health community itself—the very one that claimed to speak on behalf of health, yet refused to listen.

For Gerry, tobacco harm reduction is not a technical issue. It is—and has always been—a matter of human rights.

“The right to health includes the right to access life-saving technologies,” he argues. “Denying a smoker access to a product that is 95% less harmful is denying that right.”

From his platform at the Global State of Tobacco Harm Reduction project, Gerry and his colleagues publish reports, map access and prohibition on a global scale, and expose—with data—what many prefer not to say out loud: A system that allows the sale of cigarettes but bans flavored vapes. That profits from disease while silencing those who propose alternatives.

“Many countries ban vaping. None ban tobacco,” he notes. “How do you explain that—if not by ideology?”

In Los Angeles, you can buy lemon-flavored THC. But soon, you may not be able to buy a mango-flavored vape. In Manila, Marlboro is sold on every corner. But snus is banned by law. In Nairobi, you can die from smoking. But you cannot legally access a nicotine pouch.

For Gerry, these are not mistakes. They are political decisions. And as such, they must be debated, contested—and, when necessary, disobeyed.

The past decade has made Gerry Stimson an uncomfortable figure for many. But also an essential one, for those who believe that public health must reclaim its deepest purpose: to protect life without judging choices.

And if that means being ignored, defunded, or excluded, he accepts it. Because his compass isn’t guided by applause. It’s calibrated by the faces he sees each time he enters a safe consumption room, a vaping conference, or a smoking cessation group: faces of people who are still alive because someone, once, chose not to treat them as numbers—but as human beings.

On stage at the Global Forum on Nicotine,

Gerry Stimson leans slightly toward the microphone. There is no dramatics. No rhetorical flourishes. Just a certainty, forged through decades of struggle:

“The right to health is not only the right to be protected. It is also the right to make informed decisions about one’s own body.”

After years confronting the stigma surrounding drugs, Gerry had come to recognize another—just as insidious—operating in the shadows of international agreements: the one that condemns smokers to die if they fail to quit completely.

They are not offered help. They are required to repent.

This was the driving force behind his defence of tobacco harm reduction as a matter of positive liberty, in the sense proposed by Isaiah Berlin: not just freedom from something—disease, harm—but freedom to choose, to persist, to decide.

“There are a billion smokers in the world. Not all of them are going to quit with willpower and nicotine patches. What are we going to do—abandon them? We have to offer alternatives.”

Gerry argues that lower-risk alternatives—vaping, snus, nicotine pouches, heated tobacco—don’t deceive.

They empower.

They don’t endanger lives.

They save them.

And above all, these alternatives restore autonomy to millions of people who, for decades, have been treated by traditional public health not as citizens, but as dependents. Or as culprits.

In his recent writings, such as "The Right to Health Means the Right to Tobacco Harm Reduction," Stimson proposes a vision as disruptive as it is necessary: to integrate the human rights framework into the very core of health policy.

Because if we recognize the right not to be exposed to secondhand smoke, we must also recognize a smoker’s right to switch from smoking, without being punished in the process.

“Denying access to less harmful technologies is denying access to health,” he says. “It’s perpetuating a system of exclusion, dressed up as good intentions.”

The concept of positive liberty runs through his speeches like a low, persistent melody—the freedom to decide how to care for oneself. How to stop smoking. How to live better.

Even if that decision doesn’t fit the standards of the WHO or certain anti-tobacco activists who, perhaps unintentionally, have become authoritarian in their certainties.

To those who accuse him of “promoting consumption,” he responds without hesitation, with clarity, with calm, and with an ethics rooted in real life:

“I don’t promote anything. I simply acknowledge that many people like using nicotine. But too many get their nicotine by smoking tobacco, which is a dirty nicotine delivery system. We have an ethical obligation to offer something better.”

In a recent interview, a journalist asked him why he talks so much about dignity. Gerry paused, lowered his gaze, and replied:

“Because the core of public health should be respect for the individual, engaging with people, and enabling them. Sadly, tobacco control has a punitive mindset, preferring coercion over empowerment, even using hate and stigma as a tool to ‘help’ people change. No other field of public health stigmatises and shames people in order to ‘help’ them.”

Today, as one of the leading voices in global tobacco harm reduction, Gerry continues to write, to speak, to travel. But above all, he continues to do what he has always done: to plant doubt in those who think public health is a settled question—and to offer real, empirical, human answers.

He does not advocate for a product. He advocates for ethics. An ethic that says, without fear: To live better is also a right. Even if you do it with nicotine.

The ballroom at the Marriott in Warsaw is now full.

Outside, the city exhales a thick blend of Polish summer, century-old memory, and the restless tremors of modernity.

Inside, an older man—with white hair and a calm voice—prepares to speak. He wears no badges. There are no grand titles projected on the screen. And yet, his name moves through the room—like a persistent, familiar echo—among those who understand public health not as a mechanism of control, but as an inalienable right.

Gerry Stimson hasn’t come to repeat what is already known. He has come to remind us of what is still denied: that there is no meaningful evidence without compassion, and no legitimate health policy without humanity.

His biography is not that of a sociologist who simply rose through the ranks. It is the biography of a methodical rebel—radically human—who placed science in the service of those who suffer most and are heard least.

A man who understood—early on, and often alone—that addiction is not a moral failing or an individual flaw, but a symptom of broader systems, stitched together by multiple forms of exclusion, abandonment, and a structural violence that so often masquerades as institutional neutrality.

From heroin clinics in 1970s London to international forums on vaping and human rights, Gerry Stimson has not only been a witness. He has been a protagonist in a transformation—as quiet as it is profound—at the very heart of public health.

A transformation that gave shape—and ethical meaning—to a new paradigm: harm reduction. A pragmatic approach, yes. But above all, a deeply human one.

Warsaw, once again.

The conference comes to an end. The lights go out, the screens shut down, the booths are dismantled with the near-automatic efficiency of routine.

But in the hallways of the Marriott, the warmth of a few unceremonious handshakes still lingers, and the echo of unanswered questions continues to circle the air, waiting for a gesture, a consequence—as if searching for someone who has not yet arrived.

Gerry Stimson is not a man of grand gestures. He never was. And yet, his influence has crossed borders, generations, and ways of thinking.

Those who today advocate for more humane, more effective, more realistic policies—whether in the realm of illicit drugs or tobacco—find in his trajectory more than just a reference point. They find an ethical and operational cartography. A way of inhabiting science without betraying the people it claims to serve.

His legacy cannot be measured in statistics—though there are many. It is not defined by his more than 220 scientific publications, nor by the books, the awards, or the positions he has held.

His legacy lives elsewhere: in the transformation of how we think—and feel—about public health.

Where there was once paternalism, he planted participation.

Where there was punishment, he instilled compassion.

Where there were only numbers, he restored faces.

Where silence reigned, he raised his voice.

Over the past year, he has begun stepping away from some operational roles. But not from the debate. Not from watchfulness. Not from writing. If his path has made anything clear, it is this: those who retire from the system are often the ones most free to say what others prefer not to hear.

To retreat, little by little, is not to stop thinking. Or creating. Gerry knows—and lives—that rare truth few still remember: real science is not a closed body of knowledge. It is a conversation that never ends.

When asked what he’d like his epitaph to say, he didn’t hesitate: “Here lies someone who tried to listen before speaking.” Then, with a slightly ironic smile, he added: “And someone who believed—even when it wasn’t fashionable—that human beings – not experts – are the agents of change.”

Gerry Stimson is not a hero. Perhaps he is something even more valuable: a persistent conscience—one among many, across time—that keeps moving forward through the noise of the human trajectory. And like every good conscience, his has a flame that continues to burn. Because there are fires that destroy. And there are others, like his, that ignite those who come after.

* * *

Gerry Stimson is a public health sociologist. He never believed public health was about perfection. He spent more than forty years navigating the spaces where policies falter and real lives — messy, complicated lives — are lived.

In the 1980s, as the world confronted the cruelty of HIV/AIDS, Stimson became one of the architects of harm reduction for drug users. At a time when abstinence was preached as salvation, he argued for something more radical: the right to survive. His work helped shift the conversation from moral judgment to a focus on human dignity.

Later, he turned to another quiet epidemic — smoking. Stimson championed a new approach: replacing cigarettes with lower-risk nicotine products. It was not a call for purity but for pragmatism — a challenge to the orthodoxy that often confuses health with morality.

As director of Knowledge-Action-Change, he has led initiatives to train new leaders and expand global conversations about tobacco harm reduction. Each year, he helps organize the Global Forum on Nicotine, a rare space where scientists, policymakers, consumers, and industry voices come together — not to agree, but to listen.

Stimson’s imprint is undeniable: over 220 scientific publications, several books, a career as Emeritus Professor at Imperial College London, and a former editorship at the International Journal of Drug Policy. From 2004 to 2010, he guided the International Harm Reduction Association, broadening its mission and reach.

On April 10th, Gerry Stimson turned 80 — a milestone not just in years, but in a life spent reimagining what public health can be when it dares to side with the imperfect, the vulnerable, the human.

About Look at the Faces of Those Who Still Breathe: A Biography of Restless Science

This project was born from a simple yet urgent impulse: to acknowledge the lives, voices, and decisions that have shaped the field of Harm Reduction—often quietly, often in tension with dominant narratives, and frequently at significant personal cost.

More than an editorial endeavor, it is part of a broader effort to document and disseminate inspiring and persistently under-recognized life stories—stories that emerge from a field where innovation, resilience, and care converge in complex, often contested ways.

Look at the Faces of Those Who Still Breathe: A Biography of Restless Science is a book-in-progress. It brings together biographical profiles of individuals whose trajectories illuminate the evolution of harm reduction and the more profound ethical, political, and human questions that this field provokes.

Built from reflective observation, archival traces, and long, in-depth interviews, each profile does not aim to idealize, but to understand — to trace the contradictions, challenges, and contributions that have shaped this space over decades. These are stories of innovation, advocacy, and perseverance — told with the attention they deserve.

These are not neutral stories. They are written with rigor, care, and yes — admiration. Admiration for those who dared. For those who imagined different ways of doing science, thinking about public health, and caring beyond protocol.

I write as someone who believes that storytelling is not just a narrative device, but a form of gratitude. This book project is, in part, a tribute to those I admire and those who cleared paths that many now walk — often without knowing who first made them possible.

Why now, and why a book?

Because harm reduction needs memory, not just metrics, because science, when it is restless, produces more than data — it creates meaning. Because these stories, if not recorded, risk becoming footnotes in someone else’s version of the future.

This project is being shared as it develops for those who care and those who can help care for it. If you see value in preserving these narratives, making visible what was lived, and honoring the people behind the principles, I invite you to follow along.

And, if possible, to help sustain the work.

Thank you for being here.

Support this Project

This book is being developed independently, with care, time, and attention to detail — all of which require resources.

If you represent an institution, organization, or funding body interested in supporting critical narratives in public health, harm reduction, and human rights, I welcome your contact.

Your support can help ensure these stories are told with the depth, precision, and reach they deserve.

To explore partnership or funding possibilities, please contact the author.

Bravo! This was beautifully written!